Showalter’s new metal edginess goes better with the in-your-face frankness of his lyrics – like whiskey and soda.

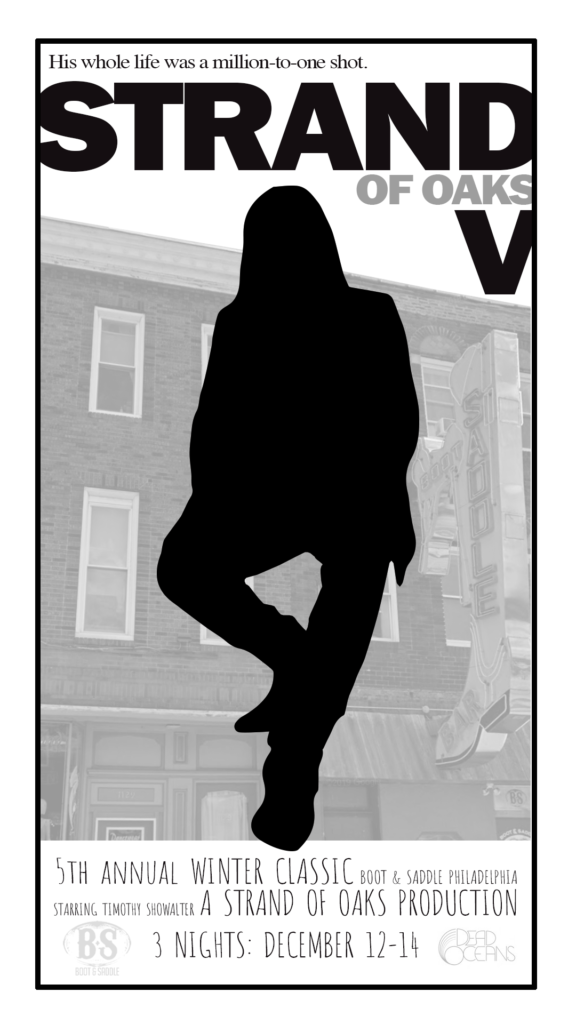

When Philly’s Timothy Showalter brings his occasionally annual “Winter Classic” residency to the Boot & Saddle this week – December 12 to 14 – the earnest, emotional rocker totes with him the mood of righteous regeneration that infiltrates his most recent album, “Eraserland.”

Long in the business of making Springsteen-ish heartland rock, Showalter’s new metal edginess goes better with the in-your-face frankness of his lyrics – like whiskey and soda. This is not to say that his powerfully bruised, fragile, yet resilient set of calling cards that he calls Strand of Oaks catalog – “Pope Killdragon” (2010), “HEAL” (2014), and “Hard Love” (2017) – are lesser than. “Eraserland” just happens to contain the punch of all-the-above and be greater than (or at least, harder and louder than) the sum of all of his parts.

A.D. Amorosi: So, Eraserland started in a sad place, but didn’t stay there.

Timothy Showalter: Yes. That’s the small, short story of the album. The full story is how much love was put into it by others, how it was created, and that it even exists. This album is one of the greatest gifts I’ve ever been given in my life.

A.D. Amorosi: You sense that if you listen to Eraserland chronologically. Go from “Weird Ways” at its start to “Forever Chords” at its end, and you find the full spectrum of feeling, from down to up.

Timothy Showalter: You’re exactly right. There is an arc, and within that arc – those bookends – it is just like life, something with a lot of roller-coasters. What’s funniest is that “Weird Ways” was the last song that I wrote for the album. An afterthought, as I had been staying in Wildwood for three weeks, with no visitors, until my wife and my in-laws came by, I had to ‘de-craze-ify’ the condo. I had been up all nights, in a wild and creative state. In the midst of cleaning, this mad rush of straightening up, I wrote “Weird Ways,” in what was probably 15 minutes. That, in and of itself, is its own mini-record.

A.D. Amorosi: I get that My Morning Jacket is involved and that they pushed you to get to the album. Can you pinpoint how that built momentum? Like them saying “Timothy, you have to do this?”

Timothy Showalter: There may be another story to this that people won’t tell me due to my sensitivity, but it is either two scenarios. My wife let people know, sent up some kind-of signal flair about me having issues and her being worried. Or, I think Carl from My Morning Jacket just casually reached out to me to collaborate. I told him I had trouble writing songs, or that I wanted to make a record and not tour for a-while. I don’t indulge Carl in my personal issues – we’re not those friends. But within 6 hours, he took the lead, contacted the studio and got other members of MMJ together to work with me. These guys all dropped what they were doing – one of them also plays in Roger Waters band – and decided to do this record with me. This wasn’t a board meeting between label suits. My label had no idea. Everyone around me just set the dates, and, it was all news to all of us, after it was ready. What I react to is purpose. Even if it is washing the dishes, that’s a purpose, finishing a task.

A.D. Amorosi: That’s what makes you act and react?

Timothy Showalter: Yes. That’s how I get on-board. I had no songs before I found out they booked a studio. Within a day, I went from feeling lost and untethered to having purpose, having something on the schedule to work toward.

A.D. Amorosi: I might not feel comfortable asking you this question had we not held long, probing and in-depth interviews going back to 2010/11. You are a deep feeling person who gets affected by lousy comments on your work. You are capable of great highs and hard lows. Do you ever wonder if maybe this process – call it music, call it art, call it expression – is too much for you? Maybe something less challenging?

Timothy Showalter: This is a concern that I have a lot in my life. What I am made to do, what my DNA is aligned toward, is making records and playing music. At the same time, it is the least healthy thing for at times for a slightly unstable mind. What attracts me the most is most detrimental and dangerous to my mental well-being, as there is no end and no beginning. No clocking out. I did construction when I was younger, and felt good at the end of the day because you could see what I had accomplished – the end goal. My wife asked me what I might do if I didn’t do music. I did teach. I think I’d like to be a park ranger at Valley Forge, as I love history and I love to talk to people and could give tours. I don’t know how it happened that Strand of Oaks got so connected to my psychological, my mental well-being. On Eraserland, I think I got better at writing those songs, without being those songs. I could purge myself of these emotions, good and bad, but I need to realize that once I do those feelings could be gone.

About Post Author

Discover more from dosage MAGAZINE

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.