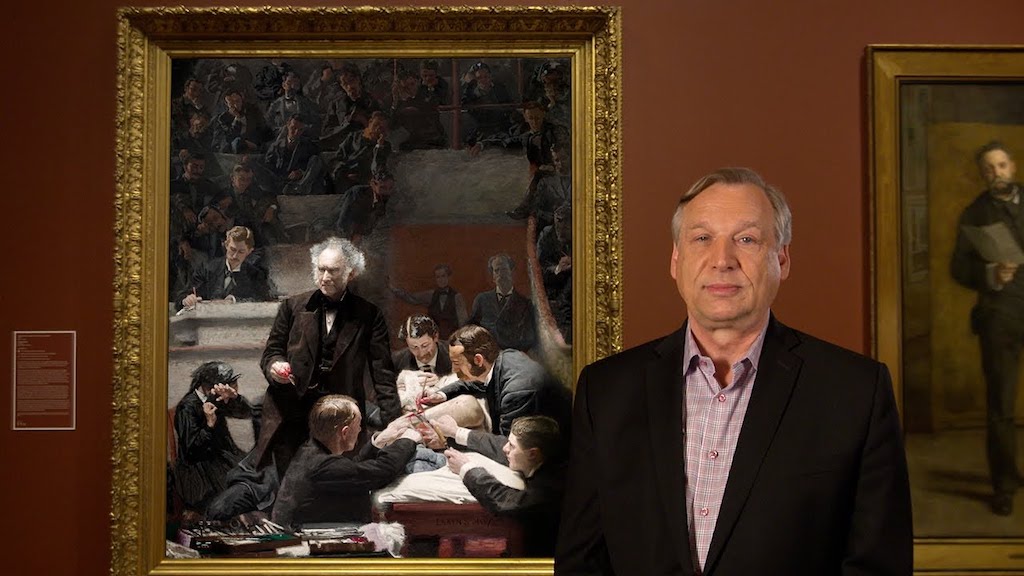

The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s George D. Widener Director and Chief Executive Officer, Timothy Rub is outta there.

In what is already a season of epic growth and great change, one shift on the sad side of the ledger came when the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Timothy Rub, its longtime George D. Widener Director and Chief Executive Officer, announced on July 30 that he plans to retire in early 2022 after his 30 year stay at the PMoA. The Museum’s Board of Trustees will immediately initiate an international search for Rub’s successor. They’ll have to search the universe to find someone as dedicated and wise as Mr. Rub.

Thirty years is a lot of nudes descending the staircase in my book.

I can remember going on to a private walking tour of the PMoA’s bowels with Timothy Rub leading the charge, talking about how everything from the museum’s infrastructure – from its unused catacombs through to re-configuring and deconstructing existing spaces – would change, and how the space’s programs and initiatives would change with it. How fresh young audiences and Philly’s racially and ethnically diverse people would become part of the museum’s aesthetic. Rub’s was as much about a charm offensive as it was an innovation offensive. Rub was there to pick up the ball left rolling by one of my Philadelphia art heroes, the late great director Anne d’Harnoncourt. When he was appointed in 2009, the Master Plan to redo the PMoA – the famously public exhibition of what I’d witnessed in private, Making a Classic Modern: Frank Gehry’s Master Plan and the “Core Project,” of adding 90,000 square feet of new public space to the museum at a total cost of $233 million – was his road to hoe. And hoe he did.

“It has been a great honor to serve as the director of one of this country’s finest art museums,” Rub wrote in a release to the staff and Board of Trustees announcing his retirement, “and to play a role in strengthening its collections and programs as well as renewing our landmark main building to make it ready for another century of service to the community.”

That same release goes on to dryly point out some of Rub’s greatest hits and accomplishments, big and small (e.g. reinstalling the galleries dedicated to the art of China, renovating the galleries of South Asian art for the first time in over four decades, renovating and reinstalling 14 galleries dedicated to European Art) achieved during his tenure in a fashion much more succinctly than I could. Rock on Timothy Rub. No one could truly replace you.

CAPITAL IMPROVEMENTS AND STEWARDSHIP

In May 2021, the museum celebrated the completion of the Core Project, a key component of the Facilities Master Plan. With Frank Gehry appointed as architect in 2006, the plan was first developed under the leadership of previous director Anne d’Harnoncourt, but had been paused upon her death and the onset of the Great Recession. Following Rub’s appointment in 2009, the Master Plan underwent further revision and development as it was readied for implementation. Rub took significant steps to make this plan public, sharing it in the form of an exhibition, Making a Classic Modern: Frank Gehry’s Master Plan, in 2014. The “Core Project,” which has now added 90,000 square feet of new public space to the museum, was executed in phases between 2017 and 2021 at a total cost of $233 million. This work, which made major infrastructural improvements and replaced aging building systems, also reorganized visitor circulation, opened up public spaces that had been closed to the public for nearly a half century, and added 20,000 square feet of new gallery space for early American art and modern and contemporary art. During construction, the museum remained open to the public, with attendance far exceeding projections until March 2020, when the pandemic forced the museum to close for much of last year.

CONSERVATION

Major projects in museum conservation were funded and completed over the past dozen years, including Thomas Eakins’s masterpiece, The Gross Clinic, in 2010; the regilding of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Diana, the iconic sculpture that presides over the Great Stair Hall, in 2012; the comprehensive cleaning of works by Rodin, including The Gates of Hell, in the collection of the Rodin Museum; the pair of important frescoes executed in 1931 by Diego Rivera: Liberation of the Peon and Sugar Cane; the outstanding suite of painted neoclassical furniture designed in 1808 by Benjamin Henry Latrobe for the Waln house in Philadelphia, between 2012 and 2017; Renoir’s Great Bathers (1884–87), in 2019, and, most recently, Charles Willson Peale’s The Staircase Group (1795), currently on view, as with the Latrobe furniture, in the new Robert L. McNeil, Jr., Galleries dedicated to American Art from 1650 to 1850.

Rodin Museum (2012–13)

One of the first and most complex projects Rub undertook during his tenure was the comprehensive renovation and reinstallation of the Rodin Museum, which has been managed by the Philadelphia Museum of Art since it first opened to the public in 1929. The exterior of the building, which was designed by the celebrated Philadelphia architect Paul Cret, was fully renovated and its interiors restored to their original appearance. The museum’s formal garden was also renovated and replanted. A major conservation project embraced both the building interior and collections, as key works by Rodin, including one of the first bronze casts made of The Gates of Hell, were cleaned and, in some cases, re-patinated. The Burghers of Calais was returned to its original location in the garden and other works were returned to their original locations in the niches on the façade and the arches in the Meudon Gate, while the popular marble sculpture, titled the Kiss, was returned to the central gallery within the museum.

EXHIBITIONS

During Rub’s tenure, a talented curatorial staff has typically originated more than 25 important exhibitions each year, many of which have broken new ground and drawn significant numbers of visitors to the museum and city. Some were exceptionally broad in concept or scope and represented major contributions in the field, including Dancing Around the Bride: Cage, Cunningham, Johns, Rauschenberg, and Duchamp (2012–13); Ink and Gold: Art of the Kano (2015); Represent: 200 Years of African American Art (2015); and American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent (2017).

About Post Author

Discover more from dosage MAGAZINE

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.