Origami butterflies fluttered overhead. There were well over a hundred, each one unique.

“What’s with all the butterflies?” I asked.

I had visited a lot of schools, first in my days as a student and then after graduating, mostly in my capacity as a volleyball coach and, most recently, as a journalist. Kellman Brown Academy’s principal, Rachel Zivic, had the sort of contagious inner brightness that would have made me immediately enroll my child in her school, provided I were Jewish – or had a child. The Jewish day school principal followed my gaze upward to the ceiling. Even though she’d walked down the same hallway multiple times a day, I imagined she never tired of observing the butterflies. If I’d been alone, I could’ve studied them for hours.

Rachel explained that each origami masterpiece, constructed out of decorated paper, had the name of a dead child written inside. As part of learning about the annihilation of more than eleven million people, six million of them Jewish, each Kellman Brown Academy seventh-grader researched the life of a child who was murdered by the Nazis then created a butterfly to memorialize that child’s life. Rachel told me that the butterfly project drew its inspiration from the poem “I Never Saw Another Butterfly,” written by a young boy, Pavel Freidman before he was killed at Theresienstadt Concentration Camp. I vaguely recalled the name of the poem but none of its words. If I ever heard it as part of my own middle school study of the Holocaust, I wasn’t paying the sort of attention I ought to have been.

When I was in the seventh grade, my sister was born and the only memories I have that even vaguely involve anything having to do with butterflies from my middle school days were putting Bob Carlisle’s “Butterfly Kisses” on our 6-CD sound system and dancing around the living room holding my still infant sister. I recall love and safety and never having to worry about people hating me for my race or religion.

The ceiling butterflies fluttered in the general way that paper does when disturbed by even the most casual of breezes. Rachel explained that each year more butterflies are added. After all, the Nazis murdered a seemingly endless number of children and each one deserves to be remembered.

We continued down the hall.

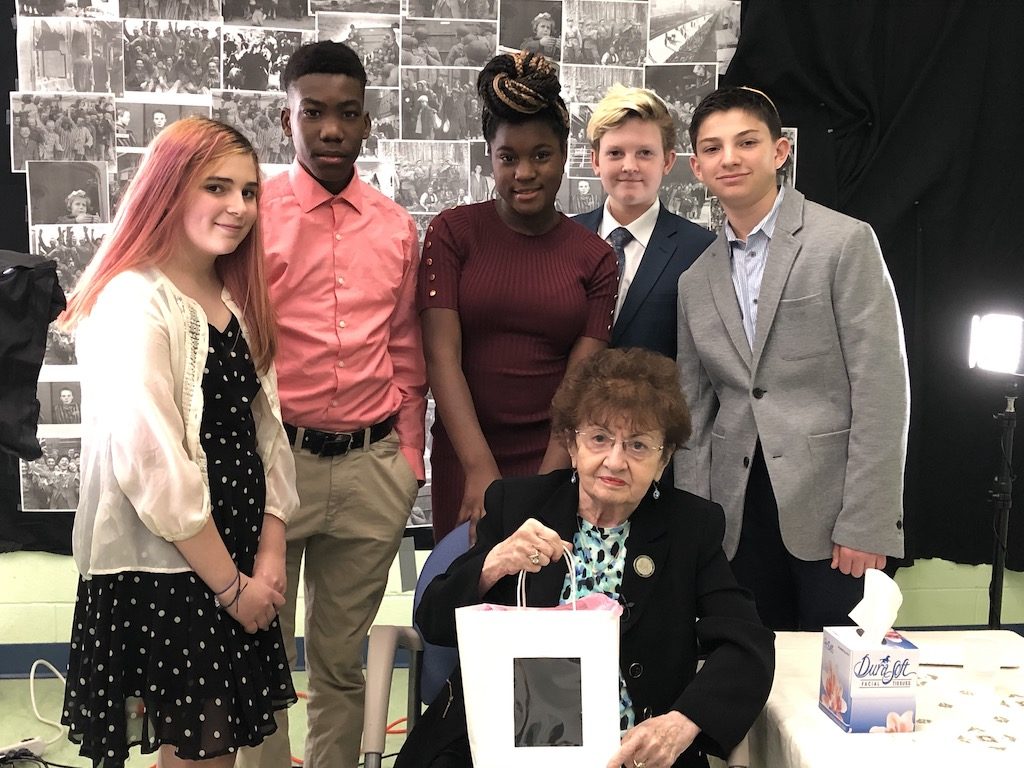

I’d visited Kellman Brown Academy to talk to a group of 17 of their seventh and eighth-grade students about their involvement in “Names, Not Numbers.” “Names, Not Numbers” is an oral history film project and curriculum created by Tova Fish-Rosenberg in which students learn about the Holocaust in a far more visceral and impactful way than they could ever hope to do through lecture-based or informational instruction. With “Names, Not Numbers,” students interview survivors then create a professional-quality documentary using the direct testimony of survivors. It combines information, innovation and empathy. To date, more than 6,000 students have participated.

I managed to emerge from my own middle school lessons about the Holocaust with the misconception that the Nazis’ systematic annihilation had been targeted only at Jews. I’d been incensed by their evil and stupefied by how they’d persecuted people but I hadn’t ever been struck by how, had I been living in Nazi Germany or any of its allied nations in the 1930s and 40s, the Nazis would’ve come for me. They’d have come for many of us. In addition to murdering and imprisoning Jewish men, women, and children, the Nazis also murdered people of color, members of the LGBTQIA community, those who were differently-abled, intellectuals, and anyone else who threatened their ideal of a white Aryan society.

The butterfly project and the “Names, Not Numbers” documentary undertaking that had drawn me to the school weren’t related. The butterflies were an entity unto themselves. Nevertheless, as I sat with the Kellman Brown Academy seventh and eighth graders, my mind couldn’t stop juxtaposing the two projects and how, through both of them, the students were recognizing that the Holocaust wasn’t some disembodied or statistical reality.

Hearing that 11 million people died can be so mind-numbing that it desensitizes a person to the reality that each of those 11 million was an individual with a name and a story.

The Kellman Brown Academy students spoke about the deeply personal effect that sitting with a survivor had on them and how collaborating with the KIPP School in Camden for this year’s iteration of the documentary added tremendous value for both Kellman Brown and KIPP. The following week, I would go to the KIPP School as well and sit down with their students, mostly people of color, and be struck by a startling reality. If any of the children from either school had been living in Nazi-occupied Europe seventy years ago, they would have had one of two fates – telling stories similar to those told by the survivors they interviewed, or, if anyone thought to remember them, being memorialized in an origami butterfly.

In the weeks that have followed, I’ve watched last year’s “Names, Not Numbers” documentary half a dozen times. I’ve Googled and re-read the poem that inspired the butterflies hanging in the Kellman Brown hallway. There’s a line I keep coming back to: “It went away I’m sure because it wished to kiss the world goodbye.”

I think about my own adolescence and the innocence of those butterfly kisses. I think about the privilege I’ve always taken for granted and how I’ve lived a life where I’ve been named, not numbered, where there’s no end to the number of butterflies I’ll have the opportunity to see. And I’m grateful but I’m also saddened and inspired.

On the wall at Kellman Brown Academy, below the origami butterflies, there is a written student pledge that all the students have memorized and say out loud each day. It is “I pledge to treat others with respect, use kind words, perform kind actions, stand up for myself and others, and be a seeker of peace.”

I think those words should be a part of all of us and that there should be no pretending that issues of hatred and bigotry, perpetrated against any people, don’t affect all people. After all, no one thought the Nazis would come for them until they did.

The “Names, Not Numbers” documentary premiere will be Thursday, March 19, 2020 at 7:00 p.m. at the Katz Jewish Community Center, 1301 Springdale Rd, Cherry Hill, NJ 08003.